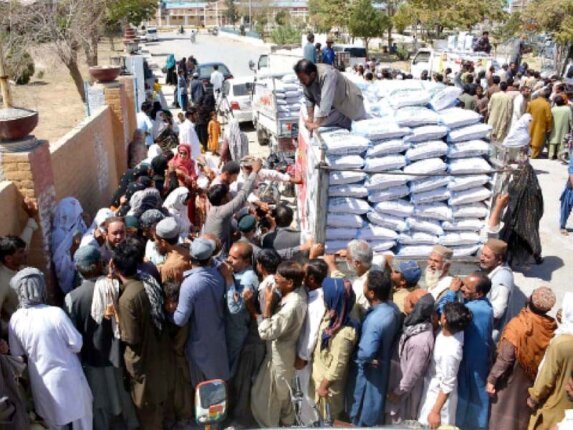

KARACHI: As the holy month of Ramazan begins, consumers across Pakistan are grappling with soaring prices of essential food items, including sugar, cooking oil, ghee, vegetables, fruits, flour, and pulses. The price of sugar, in particular, has surged from Rs. 135 per kg before Ramazan to Rs. 190, with projections suggesting it could exceed Rs. 240 per kg in the coming weeks.

Sugar Price Hike: A result of export decisions?

The root cause of the sugar shortage appears to be the federal government’s decision to permit the export of 0.65 million metric tons (MMT) of sugar in June and October 2024. This decision was based on a reported surplus of 0.94 MMT, despite a decline in sugarcane production from 88.0 MMT in 2022-23 to 87.6 MMT in 2023-24. However, industry experts and the Kiryana Merchants Association argue that the reported stock and consumption figures provided by sugar mills were inflated to justify export approvals, creating an artificial shortage.

“The current sugar stock is barely 5.8 MMT instead of the reported 7.54 MMT, while actual consumption exceeds the estimated 6.6 MMT. This discrepancy has left the majority of the population vulnerable,” an industry expert noted.

Role of government and bureaucracy in the crisis

In June 2024, Asad Rehman Gilani, Secretary to the Prime Minister’s Office, directed the Ministry of Industries and Production (MoI&P) and the Ministry of National Food Security & Research (MoNFS&R) to process a summary for sugar export at the behest of sugar mill owners. The Sugar Advisory Board, led by Federal Minister Rana Tanvir Hussain—who held dual portfolios at the time—along with MoI&P Secretary Saif Anjum and MoNFS&R Secretary Ali Tahir, moved a summary approving sugar exports. The federal government swiftly sanctioned this decision.

The subsequent price hike suggests that policymakers prioritized the interests of sugar mill owners over the welfare of the general public. Critics argue that this follows a historical pattern where politicians appoint favored bureaucrats to key positions, allowing vested interests to manipulate economic policies.

Historical Precedents: Sugar and wheat scandals

Similar controversies arose during the tenure of former Prime Minister Imran Khan, when key figures, including former Food Security Minister Khusro Bakhtiar and Special Assistant to the PM Jahangir Khan Tareen, were implicated in approving sugar and wheat exports with subsidies. An inquiry led by FIA Director General Wajid Zia revealed that sugar mills owned by politically connected individuals—such as the Omni Group, Monis Elahi, and Makhdoom Syed Ahmed Mehmood—benefited from subsidies worth Rs. 3.944 billion between 2015-2018.

Furthermore, bureaucratic maneuvering played a role in facilitating these decisions. Khusro Bakhtiar reportedly secured the appointment of Rashid Mehmood Langrial as Additional Secretary of MoNFS&R, despite his controversial past. Langrial, later promoted to BS-22, played a central role in policy decisions favoring sugar mill owners.

Wheat import controversy and government inaction

The sugar crisis is not the only issue plaguing Pakistan’s food security. The federal government and Punjab government refused to procure wheat at the official support price following an agreement with the IMF in 2024, leading to protests by farmers. Officials attributed their decision to an alleged surplus of wheat in Pakistan following imports in early 2024.

However, official records indicate that Capt. (Retd.) Muhammad Mehmood, then Secretary of MoNFS&R, initiated a summary in October 2023 for importing 2.4 MMT of wheat—1.4 MMT through the private sector and 1.0 MMT through the Trading Corporation of Pakistan (TCP). Despite opposition from the Punjab government, the federal caretaker administration approved the private-sector import. Subsequent decisions by the Wheat Board, chaired by Caretaker Minister Dr. Kausar Abdullah Malik, further facilitated excessive imports beyond Pakistan’s actual needs.

In an apparent effort to deflect public outrage, the government later suspended Capt. (Retd.) Muhammad Asif, who assumed the role of MoNFS&R Secretary in February 2024, despite his limited involvement in the original decisions. Three other lower-level officials—Dr. Waseem ul Hassan, Dr. Allah Ditta Abid, and Muhammad Sohail Shahzad—were also suspended, despite having no authority over wheat import approvals.

Political and bureaucratic collusion in decision-making

Reports suggest that influential figures, including Rashid Mehmood Langrial and Asad Rehman Gilani, worked with London-based clearing agent/alleged smuggler Israr Khan and clearing agent Hanzala Khan to manipulate bureaucratic processes and scapegoat select officials. An inquiry committee led by Cabinet Secretary Kamran Ali Afzal further implicated lower-level officials without referencing material evidence or witness testimonies.

Meanwhile, individuals responsible for the excess wheat imports—such as Saleh Farooqi, former Secretary of Commerce and Wheat Board member—were shielded from accountability. Instead, he was appointed as an inquiry officer to fix responsibility on already suspended officials, raising concerns about transparency and fairness in the investigative process.

Need for transparency and reform

The rising cost of essential goods amid policy failures and bureaucratic manipulation underscores the urgent need for accountability in Pakistan’s economic governance. The sugar and wheat crises have exposed systematic flaws where politically connected individuals profit while the public bears the financial burden. Unless corrective measures are implemented—such as stringent oversight of export permissions, independent investigations, and policy transparency—the cycle of artificial shortages and price hikes will persist, exacerbating the economic hardship of ordinary Pakistanis.